Currently reading

Hieroglyph: Stories and Blueprints for a Better Future

Ukraine: Zbig's Grand Chessboard & How the West Was Checkmated

The Girl on the Train: A Novel

Our Souls at Night: A novel

Above the Waterfall

On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft

Designs on Film: A Century of Hollywood Art Direction

The Homicide Report: Understanding Murder in America

Dead Wake: The Last Crossing of the Lusitania

The Gods of Mars

Another masterpiece from Ron Rash

How loud the sound of a fear-formed tear? How long the sorrow from a thoughtless wrong? The past. It informs, shapes, bolsters, damages, inspires, depresses and often defines who we are, who we become. In Ron Rash’s latest novel, Above the Waterfall, characters struggle with their past. William Faulkner famously said, “The past is never dead. It's not even past.” The past is indeed never finished with us until we’re done. It can no more be finished than our blood. It picks up nutrients there, drops them here, carries disease and defense, history, legacy and possibility. Is the past a medium or a message, a means or a purpose? Maybe the past gathers until enough force has been amassed and it breaks through the dam that has governed its power, spilling into the present. Becky Shytle is a forty-something with deep scars from a childhood trauma and a dodgy history of more recent vintage. She was only a school kid in Virginia when a shooter left a trail of carnage that included her teacher. Becky became mute for so long that her parents sent her away to stay with her grandparents. It was while there that she was introduced to the beauty of nature, seeing in the natural landscape a form of salvation from her terrors.All we seen is hard trials and sorrows. I’d not deny it. Burdens are plenty in this world and they can pull us down in the lamentation. But the good Lord knows we need to see at least the hem of the robe of glory, and we do. Ponder a pretty sunset or the dogwoods all ablossom. Every time you see such it’s the hem of the robe of glory. Brothers and sisters, how do you expect to see what you don’t seek? Some claim heaven has streets of gold and all such things, but I hold a different notion. When we’re there, we’ll say to the angels, why, a lot of heaven’s glory was in the place we come from. And you know what them angels will say? They’ll say yes, pilgrim, and how often did you notice? What did you seek?

And now, a state ranger at Locust Creek Park, she continues to find sustenance in nature, her spirit still trying to heal as it bonds with the beauty in the world. (I’m not autistic, she’d told me later, I just spent a lot of my life trying to be.) It is in Becky’s portions of the novel that Rash best joins his prose with poetry to create an eyes-rolling-back-into-one’s-head, toes-curling work of literary ecstasy.I had not spoken since the day of the shooting. Then one day in July, my grandparents’ neighbor nodded at the ridge gap and said watershed. I’d followed the creek upstream, thinking wood and tin over a spring, found instead a granite rock face shedding water. I’d touched the wet slow slide, touched the word itself, like the girl named Helen that Ms. Abernathy told us about, whose first word gushed from a well pump.

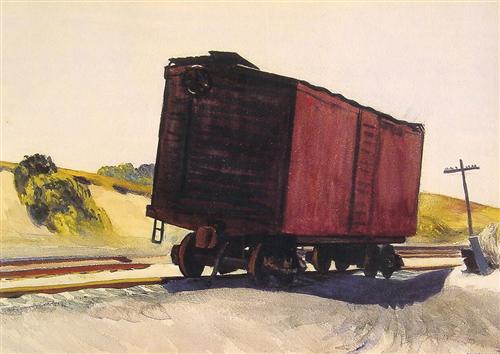

Freight Car at Truro by Edward Hopper - from Wikiart

On first seeing this in Les’s office Becky notes “Even Hopper’s boxcars are alone”

Becky feels she can share what she sees in the woods and fields with Les, a kindred spirit. Les is the sheriff in a small Appalachian town, three weeks from trading his gold star for a gold watch after thirty years on the force. He’s a decent man but carries the weight of a critical mistake he had made with his wife and a debt from his youth that he had never repaid. Becky and Les are friends, at least. They share an appreciation for the glory of nature. Les chose to build his retirement house where he did, for example, because of the view he expects to spend considerable time painting. Above the Waterfall is organized into more or less alternating chapters, his and hers. Les’s perspective is presented in a traditional narrative, but Becky’s take on things is heavily poetic. She mentions early on favoring the poetry of Gerard Manley Hopkins, a man who wrote much on the beauty to be found in nature. And while Hopkins may have been looking for Jesus in the natural world, Becky is looking for peace without, necessarily, Hopkins’ religious associations. The story centers on an assault, not on people, but on nature itself. At least in appearance. Gerald Blackwelder is in his 70s and owns a piece of land that abuts what is now a fishing resort that features a considerable stock of trout above the waterfall of the title. Someone dumped kerosene into the water, killing the fish, and harming business at the resort. The unpleasant owner of the complex is sure that old man Gerald is to blame and pressures the sheriff to arrest him. Les is not so sure. And Becky, who feels for Gerald as if he were her own grandfather, is certain he is innocent.

Ron Rash

CJ is a local from a particularly impoverished background who had toughed it out, gotten past his familial disadvantages to become a man of substance in town, working now as an assistant to the resort owner. He carries with him the scars of his past, physical as well as emotional. The past of all four characters threatens to come cascading down when a sequence of seemingly unrelated events brings them together. The town is home to some folks in the meth production and consumption business, which gives the sheriff something to do and avenues to investigate for a rash of local crimes. The depiction of Appalachian meth users is chilling. Les does his investigative due diligence and the story of his figuring out just what is what is indeed interesting. But that is not where the glory in this book resides. There are several items you might keep an eye on throughout the novel. Silence comes in for considerable attention. Not only Becky’s muteness, but pondering what silence looks like, Les’s silence in not speaking up to correct a costly error when he was young, among other mentions. Mental health issues recur a fair bit, from Becky’s PTSD to Les’s wife’s depression, to whatever it is that makes a meth addict, to some household violence in Les’s family tree. If you are a young shrink looking for plentiful business you could do worse than to set up shop here. Water references pervade. Sometimes it is just something wet, but more than likely, given the subtext, there is more to this water than something to drink, a pretty stream or a place to cast your line. Maybe a connection, a flow between being and not. And of course, there are trout.

But the big catch here is the application of Gerard Manley Hopkins to contemporary Appalachia. His work pervades the novel. References to his poems are many, sometimes overt, sometimes popping up in the arcane words he favored. I would urge you to read this short novel through once, take a bit of a side trip to Hopkins, (I have provided tickets to that boat in EXTRA STUFF below) then read it again. There is a lot going on that may evade your hook on the first cast. But in case you opt to leave your tackle in the box, a bit of a short look. You may have come across Hopkins’s main chestnut, Spring and Fall, in an English class at some point in your elementary school education. A young girl is saddened by the fall of autumn leaves, seeing, but not understanding that she sees her own demise and the demise of all in nature’s annual shedding. Hopkins, who not only converted to Catholicism, but became a Jesuit priest, looks through the tinted lens of nature in seeking the eternal. In a way this is what Becky does, and the language in which her chapters are written is suffused with the spirit, sound and feel of Hopkins’s poetry. If methworld is a hellish place, the flight of birds, stars tacked in place in a light-pollution-free sky, sun setting and a silver birch glows like a tuning fork struck offer the opposite. Birds seem to pull Becky. One even alights on her. What does that portend? Here is a taste of a Becky chapter, in fact, the opening chapter of the book, using some of the forms Hopkins was fond of.Trout have to live in a pure environment unlike human beings; they can’t live in filth! And so I think there is a kind of wonder; to me, they’re incredibly beautiful creatures. I can remember being only four or five and staring for long periods at them, just watching them swimming in the water. But also, like Faulkner in “The Bear,” the idea that when such creatures disappear, we have lost something that cannot be brought back. And I think this is what McCarthy is getting at, at the end of The Road. They mean many things: beauty, wonder, and fragility, in the sense that they can be easily destroyed. - from the Transatlantica interview

Ron Rash’s novels have a fair bit of darkness to them. There is a fair bit of optimism here, despite the challenges his characters face, and some of the less appealing goings on in the setting.Though sunlight tinges the mountains, black leather-winged bodies swing low. First fireflies blink languidly. Beyond this meadow, cicadas rev and slow like sewing machines. All else ready for night except night itself. I watch last light lift off level land. Ground shadows seep and thicken. Circling trees form banks. The meadow itself becomes a pond filling, on its surface dozens of black-eyed susans.

Most writers would be happy to have written one masterpiece in their career. Serena is certainly that. But, with Above the Waterfall, Ron Rash has produced a second. There is a golden inner glow to Ron Rash's literary world. He uses words to scrape away the covering crust so we can spy what lies inside. It is a beautiful landscape to behold.One thing I want to do is for landscape and my characters to be inextricably bound together. I believe the landscape people live in has to affect their psychology...This…novel is…about wonder, about how nature might sustain us. I wanted to look at the world a little more hopefully. – from the Transatlantica interview

Review posted – 9/4/15

Publication date – 9/8/15

=============================EXTRA STUFF

Reviews of other Ron Rash books -

----Burning Bright

-----The Cove

-----Serena

Rash does not, so far as I can tell, have a facebook page. But his son, James, set up a Fan Club FB page for him.

Here is the Poetry Foundation’s bio of Rash, who, after beginning his writing life with short stories, spent about ten years focusing on poetry, and has published several volumes. His skill as a poet is eminently clear in …Waterfall

This is the Poetry Foundation’s page for Gerard Manley Hopkins A wonderful article that explains Hopkins’ poem, The Windhover, which is mentioned in Above the Waterfall

There is a cornucopia of intel on Hopkins in this Sparknotes piece

Interviews with the author

-----TINGE Magazine – by Jeremy Hauck and Kevin Basl

-----SouthernScribe.com - by Pam Kingsbury

-----Transatlantica - by Frédérique Spill

-----Wall Street Journal - by Ellen Gamerman - Thanks to Linda for cluing us in to this one.