Currently reading

Hieroglyph: Stories and Blueprints for a Better Future

Ukraine: Zbig's Grand Chessboard & How the West Was Checkmated

The Girl on the Train: A Novel

Our Souls at Night: A novel

Above the Waterfall

On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft

Designs on Film: A Century of Hollywood Art Direction

The Homicide Report: Understanding Murder in America

Dead Wake: The Last Crossing of the Lusitania

The Gods of Mars

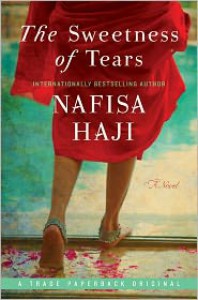

The final chapter of The Sweetness of Tears begins with the following quotation:

The final chapter of The Sweetness of Tears begins with the following quotation:(really, shouldn’t it be they who sow…?)They that sow in tears shall reap in joy – Psalm 126, v 5

There is enough sowing here for a spring planting. For a few minutes at the beginning of the book I thought this might be an edition of the new Lifetime series Chick-Lit, South Asia. But it turned out to be an intelligent, content-rich novel, reminding me very much of the work of Thrity Umrigar. Haji takes a close look at two families from different worlds, one Christian, one Muslim. Across generations each family suffers its own partitions, copes with its own secrets, makes its own mistakes, and weeps the same human tears.

The story is told in multiple-first-person format, which worked well. There are four main narrators and a fifth speaks only once. Josephine March, named for the Little Women character, is a young woman from a very Christian family, which includes peripatetic missionaries and a well-known televangelist. While studying genetics, she realizes the significance of her brown eyes, as a child of blue-eyed parents. So begins her quest and Haji’s story. We follow Jo to meet her biological father, a Pakistani living in Chicago. We learn his story and begin our journey east.

While the novel begins in the US, it is centered mostly in Karachi. Family histories are primary here, and Haji has done a masterful job of weaving her characters’ journeys into a coherent tale. She touches on the partition of the Indian subcontinent and looks at manifestations of the deep divide between Sunni and Shia, addresses the effects of PTSD from both Vietnam and the latest war in Iraq, moves from questioning one’s personal history to interrogating prisoners.

Religion plays a very large role in this comparison of East and West. Most of the focus is on the Eastern portion, but care is taken and respect is given to different traditions, with considerable attention to how religious practice and law informs the lives of the characters. It was illuminating.

If you have a tough time keeping everyone straight when there are a lot of characters (like me) it you might struggle here. I suggest keeping a list of who’s who and update it as needed. I assure you that it will be worth the trouble. I found her major characters to be rounded and interesting, and I often wanted to know more about them, which is always a good thing.

The narrative flowed quickly and held my interest, but I was put off by a plot decision or two. In one, a character who had been barely mentioned, marries a young pregnant woman with barely any indication that there was a prior attraction. In another instance, a prisoner mentions a connection that was just a little too convenient to be anything but a crude plot manipulation. But such qualms are few. Haji ties her plot lines and characters up nicely and makes very well her point that we have much more in common with people, from what appear on the surface to be extremely crossed cultures, than we might imagine.